“What are you doing to us, Gary!?” These were the first words that left my mouth as I crossed the finish line. “We’re just making you stronger, one race at a time,” Gary replied as I accepted his congratulatory hug. 17 hours and 43 minutes earlier I’d set off in the middle of the night, along with 100 or so others, on the second annual running of Gary Robbin’s 110km mountain race in Whistler, BC. This was my longest pure race to date and by far the most challenging.

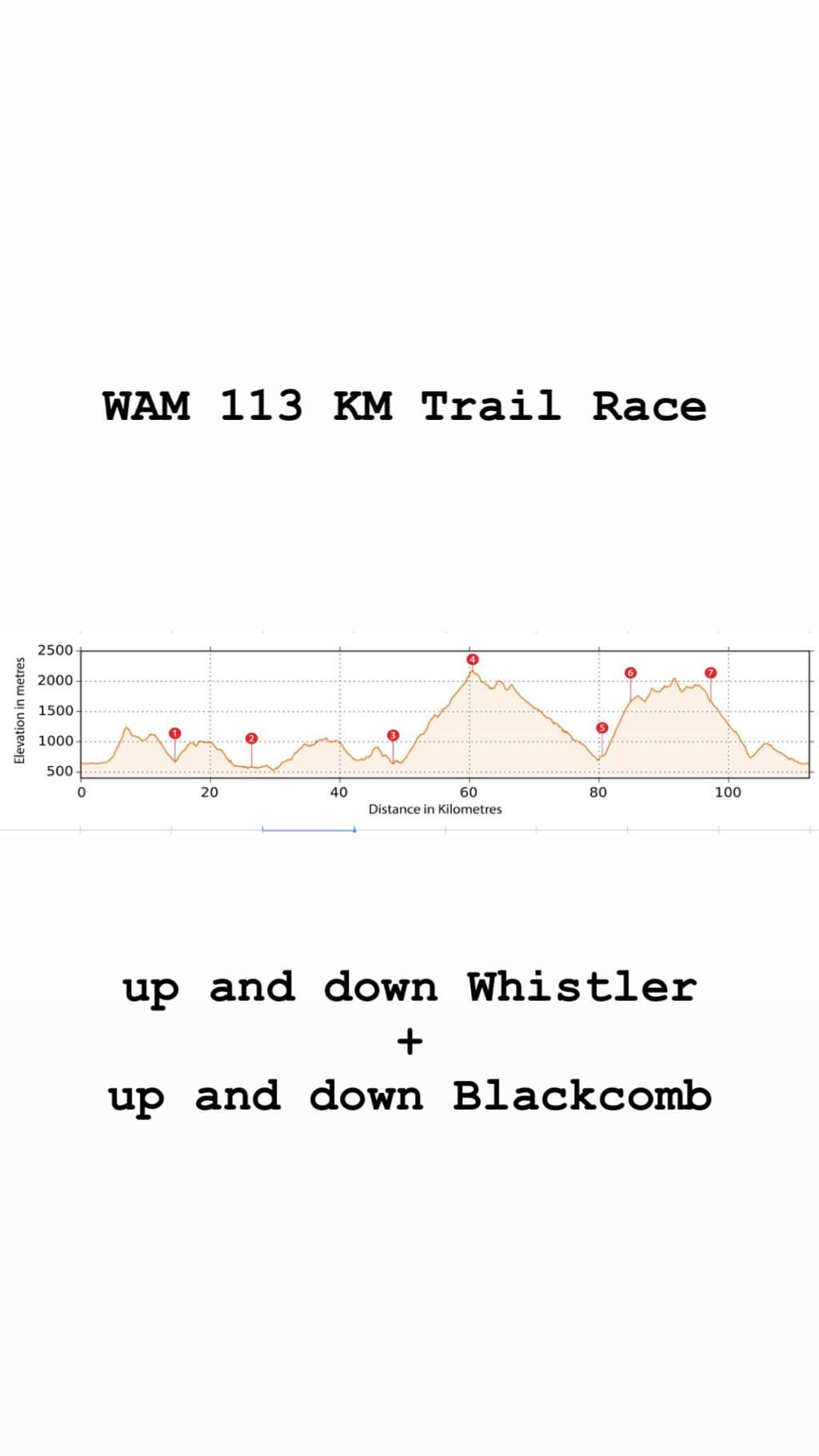

Whistler Alpine Meadows — “WAM” for short — included five races: an ascent race, a 25k, 55k, 110k (ish) and 160k (ish) and each promised a “true mountain running experience”. All races traversed the rugged terrain of the Blackcomb/Whistler area and the distances tended to be rounded up by 5-10kms so, we all got our money’s worth and then some. But first, let me tell you about Gary.

Meet Gary

Gary Robbins is the race director for the Coast Mountain Trail Series and organizes a number of rugged races in the Vancouver/Squamish/Whistler region. If you run the trails in this area, chances are you’ve at least heard of him. In the ultrarunning community, however, Gary is well known for a number of impressive feats. He has many wins and podium finishes under his belt and has set some impressive fastest known time (FKT) records, including an 18h50m supported run of the challenging 93 mile Wonderland Trail. The route, which circumnavigates Mount Rainier, took me and a few friends 3 long days to backpack earlier this summer. In short: Gary’s no slouch.

Gary Robbins. Image from Running Magazine

What’s most interesting about Gary is that he doesn’t have a running background. He ran his first ultra about 15 years ago while in his mid twenties when ultra running was much more of a fringe sport than it is now. After only a few years, he was winning or placing well in local races, and then in 2010, he won the aptly named “HURT 100” in Hawaii and finished top 10 at Western States, one of the most competitive races in the world. I ran my first trail race when I was 27. I’m 31 now, so I can appreciate the amount of work he must have put in to get so good so quickly.

Over the past few years, Gary has turned his attention to the infamous Barkley Marathons, the brain child of “Lazarus Lake” whom I had the privilege of meeting in Calgary this past spring during the Outrun Backyard Ultra. Gary, at this point, is the most famous person not to have finished the Barkley. He’s attempted the nearly impossible 100+ mile event three times, completing a remarkable four of five loops in his first attempt. He is better known, however, for his second attempt when he completed 4.9 loops, going off course two miles from the end and hobbling to the finish from the wrong direction , a mere 6 seconds after the 60 hour time limit. There’s a heartbreaking video of the event here: Gary’s almost finish. He has since turned this moment into a bittersweet pre-race joke at his own races when telling runners to be respectful to the volunteers that enforce the time cut offs. “I missed a cut off once,” he’ll say with a smile.

Voluntary Suffering

At this point, most people who know me are aware of my running exploits. I post pictures online of myself on the trails, I write blog posts like this, and it naturally comes up in conversation. I try not to let my adventures take up too much space, but it’s inevitable that I get asked the “why?” question.

I can wax poetic about the lure of the mountains and the beauty of the trees, but that’s really only half of the equation. There’s a deeper aspect too. No matter how you measure them, these races are hard. And that’s the draw: suffering is the foundation of the sport. It is this open embrace of pain that makes it quite unique. I don’t enjoy pain, but I know I grow stronger when I embrace it consciously. This voluntary kind of suffering is the the special ingredient of extreme endurance sports that keeps me coming back for more.

Not that it’s all suffering, of course. In a typical ultramarathon, there are several dynamics unfolding simultaneously. First, you’re competing with yourself, striving to accomplish your personal goal for that particular event, which may just be to finish. Second, you’re competing with the other runners, jockeying for positions (though usually in a friendly, supportive sort of way). And lastly, you’re doing battle with the course itself. It is the collective adversary, that each runner must overcome one step at a time. When we battle the course, we are, by extension, facing off against the course’s creator. In the case of WAM, this is Gary.

Of course, race directors do not organize these events alone. Gary has a tremendous amount of support from his team at CMTS and all of the generous volunteers. But when you’re out on this course, you’re out on his course. He is the auteur. When you have to slog up a steep incline without switchbacks, it’s Gary who’s to blame. I’m sure just about every ultra-runner can attest to cursing the name of a race director late in a race when facing an unexpected hill, some gnarly rocks, or just about anything other than smooth, flat, “easy” trail.

A good race course is like a good teacher or a good coach: tough, but fair. They exist to push you outside of your comfort zone for your benefit above all else. Like a devout disciple from the Lazarus Lake School of Suffering, Gary Robbins also wants us to push ourselves further than we would otherwise. He might appear to be a sadist, but he walks the walk, and he understands the ways we grow as people when we stretch our perceived limits.

But enough about Gary. He’s a dangerous man. That’s all you need to know.

Training for WAM

Last year I only ran two races, one of which was the Squamish 50 miler (80km) — the best known of the CMTS races. After a year of injuries and mixed feelings about running in general, it marked my return to the sport. It was a great race, rugged and steep, but mostly a lot of fun. I had intended to return this year, train for it specifically, and improve my time, but fate intervened the day registration opened for 2019. I slept in and the 450 tickets were sold out before I’d taken a sip of my morning coffee.

I was bummed, but there’s no shortage of races to run these days. After clicking around on the CMTS website, I noticed they also organized a series of races in Whistler. The 170km “100 miler” — new for 2019 — caught my attention, but when I saw there was 9500m of vertical gain, I registered for the the 110km race instead. It “only” had 6000m of gain. This is still more climbing than most 100-miler races, however, so I knew it was going to be a long day. And like that, WAM became my “A” race for the year.

I’d sat around most of the winter and my unstructured, “run when you feel like” approach to training wasn’t going to cut it if I expected to finish, let alone compete in the race. The amount of up required for WAM was twice as much as anything I had done before, so I was also going need to find some mountains.

My spring was filled with travel which kept things interesting as I eased back into running 6 days a week. I ran the service roads around Merritt, BC as I waited for the snow to melt; I ran around the town of Terrace in Northern BC; I ran the technical mountain bike trails in Cumberland on Vancouver Island while visiting with my uncle and aunt. I even squeezed in a few long runs in the spectacular Jasper National Park.

Over the summer, Ella introduced me to two books: (1) Training for the Uphill Athlete by Steve House, Scott Johnson and Kilian Jornet; and (2) Training Essentials for Ultrarunning by Jason Koop. As Ella will tell you, there are some conflicting philosophies between the two books, but when it comes to uphill training, both agree that you need to do it, and do lots of it. With all the travel, staying organized had become increasingly challenging, so I combined these books with a TrainingPeaks subscription to plan my schedule. Coaches are expensive, so “coaching myself” was the more economical option.

After the Outrun Backyard Ultra in Calgary, I drove up to Yellowknife, back down to Vancouver, and then spent a few weeks of hanging out in the Seattle area. This trip included the White River 50M and backpacking trip on The Wonderland Trail, a spectacular (and spectacularly steep!) circumnavigation of Mount Rainier. From there, I packed up and made my way down to Southern California to see my parents and rack up some serious “vert” in the final weeks before WAM. In the month of August, I climbed Mount Shasta, ran up Mount Whitney, hiked up San Gorgonio and ran up San Jacinto (twice!). By the end of the summer, my body had become hardened in a way I hadn’t felt since the PCT. I was excited to see how all this hard work would translate on race day.

Mount Whitney peak

Race Weekend

My original plan was to drive back to Vancouver for the race, but part of the reason I drove to California in the first place was to work on the van itself. My renovation project was turning into a never-ending affair. As race day loomed closer, the van was nowhere near ready for me to drive back home, so I decided to fly instead. I booked a flight, a rental car, and a room at the Whistler Athletes Centre. The only missing piece was a crew.

Ella had volunteered to help me earlier in the year, but the dates were no longer favourable for her. Going solo would have been fine, but not nearly as much fun. I thought about who else I could ask and then bingo: Malcolm’s name popped into my head. A friend and fellow runner with a flexible schedule, Malcolm knew a great deal about the lore of ultrarunning, but hadn’t yet experienced either running or attending an event. I floated the idea by him and he was immediately game.

In the week leading up the race, I shared my planning spreadsheets and forwarded him Gary’s pre-race emails about bear safety, shuttle bus logistics, gear requirements, course changes, aid station adjustments, additional course changes, snow reports, and other related material. I’m happy to say, in spite of all this, he was still gung-ho! Meanwhile I was finalizing my gear list, nutrition plan, and pace goals for a course I’d never seen before. Days before my flight, I had a strange dream that Malcolm and I arrived late for the race and I had to negotiate with Gary for permission to start running (he wouldn’t budge).

At the last minute, I received a welcome surprise from Jean-Nic, my old running buddy in Montreal. He introduced me to a fellow 110k runner named Martin who would also be flying in from Montreal. I offered Martin a ride to Whistler and he happily accepted. We were now a team of three. Even better!

I flew to Vancouver on Thursday where I spent the night with my long time friends, Chris and Victoria. After catching up with them and a few of their friends over Indian food — a risky choice in hindsight — I called it a night and got some sleep. Friday morning, I loaded up the car, ran a few errands and then picked up Malcolm and Marty. Traffic was terrible getting out of the city, but the three of us were all enjoying the conversation, so it didn’t matter.

We arrived at the Hilton in Whistler for packet pick up around 6pm. It felt like we had lots of time, but we had be awake in 8 hours and we still hadn’t prepared our drop bags or eaten dinner. We walked back to the car and sorted through our gear in the parking lot. Drop bags could be sent to the 49km and 82km aid stations where I estimated I’d arrive at roughly the 6h and 11h marks, respectively. I sorted my gels, bars and other race food into three piles, and put two into my bags adorned with rainbow coloured ribbon to make them easier to find later.

We went back to to our hotel, dropped off the bags and drove into the village to find somewhere to eat. I was suddenly starving. I wolfed down a slice of pizza and a panini. We relaxed and chatted about the minutiae of ultra running. Next thing we knew, it was 9pm, only 5 hours until wake up time, and none of us had checked into where we were staying. We drove Marty to his campsite at the Riverside Resort where the race would start and finish the following day. Malcolm and I then went to pick up some groceries for the morning and drove back to the Whistler Athletes Centre (WAC).

When we arrived, there was a crowd of people gathered outside the building waiting for the leader of the 100 mile race to arrive. I spoke to a woman there whose nephew was the one they were expecting any minute. She told me we were at the 90km aid station. It was 10pm and that race had started at 10am that morning. 12 hours in and only those at the front of the pack were around the halfway mark! I wanted to stick around, but when I told the woman I was running 110k race, she simply asked, “Shouldn’t you be in bed?”. I laughed, but sure enough, 5 minutes later, Malcolm and I went upstairs and got everything sorted for the following day. By the time I finally lay down to sleep it was almost midnight. So much for getting a good night’s sleep.

Race Time

Race day started at 2am. My alarm went off after only two hours of sleep. I stared at the ceiling for five minutes, took a deep breath, then got up to face the day ahead. I put on my running gear which I’d neatly laid out the night before then knocked on Malcolm’s door. “You up?” He was ready to go. We went downstairs to the shared kitchen of the WAC to eat some breakfast.

Malcolm had already started filming and documenting the day via Instagram stories. Video of me walking down the hall; video of me in the elevator; video of me eating a parfait. “Is it true you started running to become an Instagram influencer?”, Malcolm asked. I laughed. This cinéma vérité approach wasn’t exactly what I was in the mood for at two in the morning. We joked about how “utterly unwatchable” ultrarunning is as a sport, so perhaps this would liven things up.

In the kitchen, we sat down at a table with two other runners and chatted to them while we ate. “We may not have to run as far as the 100 mile runners, but we’re getting just as little sleep,” one of them joked. At 2:45am, Malcolm and I loaded up the car and drove to the shuttle bus pick up point in the village. I don’t remember what started it, but we found ourselves deep in a conversation about The Big Lebowski. Our discussion continued on to the bus, to the Riverside Cafe, and then to the race starting area. “Did you ever hear of the Seattle Seven?” We weren’t just quoting the script; we were really getting into it. Was I merely distracting myself from the hours of suffering to come? Maybe, but I also never turned down an opportunity to discuss all things Dude.

Gary Robbins gave his pre-race talk at 3:45am. It was as information-heavy as his 15 pre-race emails. We looked around in the dark for Marty and when we found him, Malcolm took a picture of the two of us. With minutes to go, we wished each other luck, and then at 4am sharp, we set off.

I’d never experienced such a lack of pre-race nerves before. We started running and I soon realized I hadn’t started my watch. I was still in Dude-land, laughing to myself about the “Little Lebowski Urban Achievers”. Gary rode ahead of us for a couple kilometers on a lit up bike. We cruised along a paved path when up ahead we heard Gary yell, “Bear! Bear! Bear!” I couldn’t see anything, but I also figured a bear wasn’t about to jump a conga line of 100 humans.

I started near the middle of the pack where the pace was surprisingly fast. I kept reminding myself that it was going to be a long day and these early kilometres would be negligible by the end. I figured the race wouldn’t really start until the 80km mark, and almost everyone goes out too fast anyway. Plus, I’m like a diesel engine: it takes me a good hour to properly warm up.

The conditions were cool, but not cold. The trail was soft and damp, but not water logged. “Beautiful evening”, I said to another runner as I came up alongside them. And I meant it! The forecast had been iffy, but so far, this was perfect running weather. I took it easy for the first few hours, walking the hills and chatting with the people around me. There was a pilot from Florida, a Kiwi who lived in Squamish, an American from Seattle. My body was moving well. I fell into a rhythm quickly and started passing people.

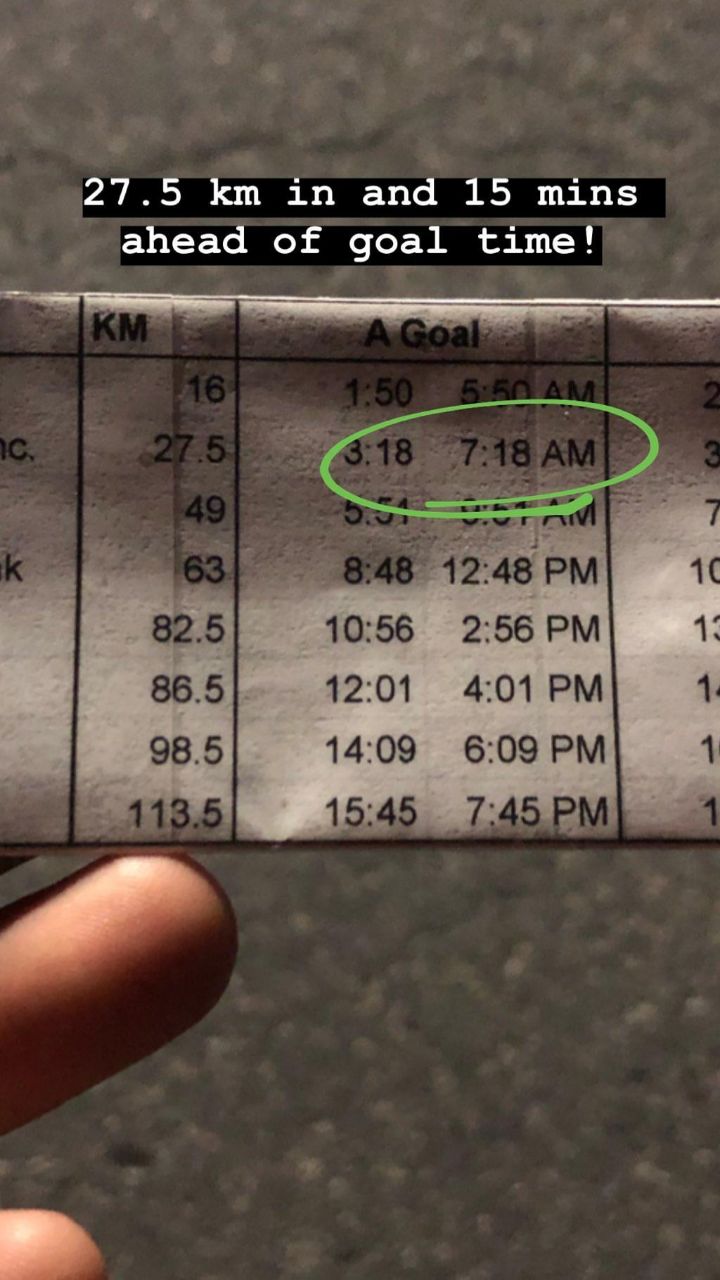

Pre-race with Marty and the time goal sheet I made for Malcolm

I arrived at the first aid station 15 minutes ahead of schedule. My watch said 13km when it was supposed to be 15km. I knew we’d make up those extra miles later, but I was a little annoyed as it might affect my ETAs for linking up with Malcolm later. I’d told him not to bother meeting me at this stop, and to go back and get some sleep. I handed my water bottles to a volunteer for a refill, grabbed a few snacks, and set off again.

The previous day, I’d given Malcolm a printed copy of the aid stations with my “A” and “B” time goals. I explained that these were very approximate since I hadn’t trained on the course or even seen the course, and was partly basing the splits on last year’s results which followed a different route anyway. My “A” time goal was 15h45m and my “B” goal was 18h10 (20% slower than the “A” goal). I wanted to finish in the top 10 with an eye on the top 5. If I could come close to my goal time, this was a definite possibility.

Aside from the steeper bits, the trail up to that point had been very runnable. The last few kilometres before the second aid station, however, were comically rugged and technical by comparison. We kept criss-crossing between a railroad track and a dense wooded area. The sun had started to rise by this point, but I still had my headlamp on. It was good timing too as my batteries had started to fade and I found it hard to see when going through the denser patches of forest. I took my first fall of the day here while trying to negotiate some large roots. “This feels more like a Gary Robbins race,” I thought as I dusted myself off.

The second aid station — Function Junction — was at 27.5 km. My ETA according to “the sheet” was about 7:15am and Malcolm was slated to meet me there. I grabbed some food and looked around, but I couldn’t see him anywhere. Damn. I was still 15 minutes ahead of schedule, but I thought he might have showed up early. I ate some sausages and potatoes and refilled my bottles. I had planned on filling my third water bottle as the next section was 21km long and I’d estimated 2h30m to complete, but I couldn’t find it anywhere in my back vest pouch. I filled my two front bottles — for a total of 1 litre— and counted on finding a stream along the way to grab more. I looked around for Malcolm again, but I didn’t want to linger. I sent him a text to explain that I’d set off for the next stop at the WAC at 49km.

The next section began with a few kilometres of incredibly smooth, hard trail. My pace dropped below 5 min/kms and I had to remind myself to take it easy and keep my heart rate down. After 45 minutes alone, I fell in with a group of about about seven runners. The course transitioned to wide service roads and then to a unique passage through the trees that was spongey and moss-covered. It was hard to actually run the stuff, but it was particularly beautiful, and captured the unique qualities of the Pacific Northwest.

Bees?

It was around this time, about 4h30m in, that I faced my first obstacle of the day. I was adjusting my shorts when I felt a strange prick on my inner thigh. It was benign and far from painful, so I didn’t give it another thought. 15 minutes later, however, my throat started to feel strange, like something was lodged at the back. All I’d eaten was a gel — the consistency of honey — so that didn’t make much sense. I started coughing, intermittently at first, then it was every few seconds. I could breathe in fine through my nose, but my throat was closing up and I choked hard every time I tried to breathe in through my mouth.

When the single track trail spat us out at another service road, I keeled over and tried to cough hard in case there really was something in my throat. A couple of the guys around me stopped to see if I was alright. I considered asking one of them to perform the Heimlich manoeuvre, but I wasn’t sure that would do anything. “I’ll be fine”, I said, not entirely sure if I was being stoic or stupid, or both.

I stopped there for a minute and focused on taking deep breaths, in through my nose and out through my mouth. We were maybe an hour away from the WAC (aid station #3) where I’d seen paramedics stationed the day before. We were in the middle of the woods, so either way, I’d have to hang on until then. I started running again, finding a comfortable pace while I focused on my breath. Within 30 minutes, I was breathing much better and wasn’t coughing as much.

I arrived at the WAC at about 10am. We were 6 hours in, and the place was crawling with people. Someone took my water bottles and I looked around for Malcolm. There he was! On the lawn, sporting his bright orange jacket and an equally bright smile. It was so great to see him. He beckoned me over, so I walked to where he had laid out a very professional looking spread of bars, gels, gummies and other running accoutrements.

Malcolm’s excellent spread

I told Malcolm about the morning’s events, how I was feeling, and how my throat had closed up. He told me my throat was red and swollen. I was breathing normally by this point, but I was still a bit nervous about the whole thing. I asked for the paramedics and a man nearby went to get them. My new hypothesis was that I’d had an allergic reaction though I’d never had one before, so I was still speculating. The medics arrived promptly. One of them checked my pulse and looked at my throat while the other asked me questions. They told me that all the adrenaline my body was producing from all the exercise had actually brought down the swelling naturally. They said it was probably hives, but that my heart rate was normal, and nothing to worry about. They offered me Benadryl which I gratefully accepted.

With a clean bill of health, I got my bearings and prepared to set off for the biggest climb of the day: 1500m (4900ft) to the top off Whistler Peak. I saw some pizza at the aid station, but stupidly left without taking any. Looking back, I’m not sure if I actually ate anything at that stop, but I’d filled my pockets with plenty of running food. Malcolm said I was probably in around 15th place, but the group at the front were only about 30 minutes ahead. This was good news. Despite the hives debacle, my legs felt fresh and I was raring to go. I said goodbye to Malcolm and headed back into the woods.

Whistler Whiteout

I estimated the 19km climb would take almost three hours, so I put my headphones in and got to work. I completely forgot to grab the extra water bottle from my gear bag (which Malcolm had been lugging around all morning). I had enough water for a couple of hours, but given the steep terrain, I knew I could quickly get dehydrated if I didn’t find some along the way. It was early in this section I fell in behind Freddie, a quiet guy from California who I’d go on to spend the next 7 hours leapfrogging. The trail was much steeper than I expected and I quickly ran out of water. Apparently Freddie did too. We were standing over a puddle of murky brown water. “If I go down, you go down with me”, he said with a smile. I decided we could do better and held off. There had been plenty of flowing water in the previous section that I had filled up from. Surely there would be more up ahead.

An hour later, my throat was dry and my bet hadn’t paid off. The climb was brutal and only got more challenging as we got closer to the top. We were soon above the tree line where it was completely socked in. I tried to get my bearings in the fog. For some reason I’d thought the “peak” was the Roundhouse Lodge, but judging by the rocky terrain and the ski run signs, it was clear we were headed to the actual peak of Whistler. After three hours of ascending, we reached a road and a white tent appeared in the distance. We arrived to find a crew of five volunteers cooking pancakes and ramen noodles. They were bundled up in warm jackets and within minutes I understood why. It was freezing! I drank half a litre of water right away and put in a request for a pancake and cup of soup.

Up, up and more up on the way to Whistler peak

There was a fire nearby where a group of 100 mile runners were bundled up and chatting. I was 9 hours into my day; they were 27 hours into theirs. “How’s it been going?”, I asked. Pause. “It’s been really hard,” one of them replied. No kidding! 100 miles is hard enough when it’s flat, let alone when you add steep climbs and technical terrain. After a few minutes of chatting, my core temperature started dropping, so I put on my jacket, gloves and a buff around my head. It was hard to leave, but I needed to keep moving. I was behind schedule and wanted to make up time on the descent. I saw Freddie leave, so I filled up my bottles, thanked the volunteers, and made off after him.

There was zero visibility on the way down, but the course was easy to find. Gary wasn’t kidding when he said they’d placed 10,000 flags along the course. I knew we were heading down to Whistler Village, but given where we were on the mountain, I had no idea how we would get there. We soon discovered there was still plenty of ascending to do before we actually went down. In the fog, I lost all bearings and just focused on moving forward. I was actually moving very quickly and I passed Freddie and another runner. After a few kilometres of rocky terrain, the trail evened out into a winding single track with a consistent grade. We were going down, and fast.

After an hour, I was feeling alright, but I wasn’t moving as efficiently as I wanted to. My quads were taking a beating and started to ache. I rolled the dice and took an ibuprofen which always carries a risk of disrupting one’s stomach. While I had stopped, Freddie and the other runner came flying past me. I hadn’t heard them coming and it made me jump. Somewhat dazed, I got back on my horse and continued on behind them. Within no time we were at the base of the village.

We then had to hike up a mean climb to get up to Blackcomb Base II where the aid station was set up at 82km. I finally rolled in with Freddie and the runner I’d deduced was from Quebec. It was about 3:30pm and the sun had poked its way through the clouds. It was glorious. Malcolm was there, with my goodie bag and all. I filled my water bottles, looked around for some pizza or any other real food at the aid station, but settled for cold potatoes, chips and candy. Slim pickins.

I sat down on the steps where Malcolm was set up, surrounded by people that he had evidently been getting to know. I was greeted with lots of smiles and words of support. I ate some Oreos, changed my shirt, grabbed a fresh headlamp and filled my pockets with more gels and bars. I was 40 minutes behind my A goal, but Malcolm estimated I was somewhere between 9th and 14th place, and that the top three had fallen back to the 4th-6th spots. Exciting! Again I saw Freddie head off ahead of me, indicating my cue. I packed my things, gave Malcolm the nod, and set off.

Blackcomb Blues

The section from Base II to 7th Heaven is the steepest of the entire race, gaining 850m in only 4.5km, similar to North Vancouver’s famous Grouse Grind. It was really hard work. I took a few breaks to simply lean on my poles and let out a big sigh. Halfway up, I passed the guy from Quebec who looked exhausted as he leaned against a large boulder. We exchanged a few words and I marched on. I got to the top of the climb in about 1h10m, putting me at 87km in about 13 hours. I saw Freddie leave the aid station just as I was arriving. He gave me a fist pump of encouragement as he set off along the service road. What a guy, that Freddie!

There were three volunteers at this remote outpost. We would return to this aid station once more before the final stretch. One of the volunteers told me I was in 9th place and within striking distance of those ahead. This was great news. The last climb had been tough, but I still had lots of energy left and was ready to make moves. As I got ready to leave, the first place runner — Mike Sidic — popped out of the trees. He looked strong and was apparently a full hour ahead of second place. I told him to keep up the good work and asked about the section ahead of me. His sigh told me all I needed to know.

As I left the aid station, another runner came up behind me, a man named Dominic from Whitehorse. As we walked up the hill, we chatted about life in the North and the steep races he’d run Europe. The road levelled out and I decided to run. “Go ahead, I won’t be trying to catch you”, he said. I laughed and replied, “You say that now…”

I quickly caught up to Freddie and we started running together. The terrain was relentless: rocky, steep, and not even a trail in some spots. The whole course was a mystery to me, but this section was particularly disorienting. I knew Blackcomb’s ski runs well, but I had no idea what the trail system was like on the backside of the mountain. Despite the challenge, however, it was one of the most scenic sections of the entire course.

The view from the Overlord trail during the 7th Heaven section

Freddie and I soon passed the 7th place runner. He looked rough. We’d been passing a lot of 100 mile runners up until this point, so I assumed he was running that race given his pace. But sure enough he had the same white bib as us. I later learned he had been leading the race for a while until he started to slow — a tough way for an ultra to play out. But regardless, Freddie and I were moving well. We just had to keep up the pace. We were in 7th/8th place and I made an enthusiastic comment about reeling in the 6th place runner. Unfortunately, not long after this my day took a turn for the worse.

My stomach had started acting up during the Blackcomb ascent. A small knot had formed right in my solar plexus and I was having difficulty chewing. It was manageable at first, but it only got worse during the 7th Heaven section and within in hour, food had lost all appeal. I’d only eaten half a Larabar and a few potato chips in the previous two hours, no where near my 250 calories/hour goal. I needed to get a gel or something in me or I’d bonk, but I just couldn’t do it. I forced myself to keep drinking water, and told myself I’d sort it out when I returned to the aid station. I estimated there was another 3 hours to go — far too long to simply try and hold on.

Freddie let me lead for a while as we descended down a particularly technical section. It was comprised of mostly large boulders. Ascending was fine, but descending was tricky. I stepped on a benign looking rock and lost my balance, slamming my knee into a large boulder. “Ahh!” It was incredibly painful. I stopped and tried to shake it off, letting Freddie resume the lead. I hobbled for a bit, but fortunately my good friend “adrenaline” came to the rescue and numbed the pain. I hobbled for a short while longer and then started moving normally again.

I completely underestimated the section. It took well over 2 hours to travel its 12km. By the time I arrived at the Rendezvous on Blackcomb, Freddie had slowed down and I could no longer see him behind me. The sun was starting to go down and a chill was in the air. I returned to the 7th Heaven aid station, my stomach a complete mess. It felt like someone was squeezing my intestines. I took an antacid and I drank some Coke, hoping it would settle things. I was sitting for only a minute when Dominic came flying out of the woods behind me. In a whirlwind, he grabbed some water and a few snacks, and was off again in no time. I was stunned. I wanted to chase after him, so I forced down as much Coke as I could and set off again.

Comfortably Numb

We started down a service road as a thick fog rolled in. My quads were aching, but this was some of the easiest terrain we’d seen in hours, so I wasn’t going to complain. As I rounded a wide turn, I looked back up the mountain and I saw some strange lights in the trees. At first I thought it was a lit-up tree house — this made perfect sense to me at the time — but as I moved nearer, I realized it was a truck! It must have gone off the side of the road. It was eerie. My first thought was to find someone to notify, but there wasn’t exactly anyone around. Fortunately, there didn’t appear to be any people inside the car, so I made a mental note to inform the folks at the finish line.

After a few more wide turns on the road, we took a trail into the woods. The sun had gone down by this point, so I turned on my headlamp. At first the softer ground was a relief from the gravel road, but this reprieve was short lived. The trail sprouted rocks and thick roots and sudden drops. I didn’t see anyone for about half an hour, and then in the distance I saw some headlamps. What was strange to me was that the headlamps were above me. We had more climbing to do? I was so sure it was all downhill to the finish. My legs were up for the challenge, but my stomach was screaming louder than ever. I just wanted this whole thing to be over.

I caught up to the headlamps which turned out to be a group of 100 mile runners. This was around the 36 hour mark for these brave souls, and the second time the sun had set on them since the start of their runs. “Good job! You got this! Keep it up!” I said as I passed, unsure if these words of encouragement were more for them or for me. A few minutes later I looked behind me and saw a headlamp barreling towards me. Was it Freddie? Nope, it was the Quebecer I’d seen leaning against the large rock 3 hours ago. He passed me at an incredible speed given the terrain. Talk about a second wind!

My plan to move up the field late in the race had backfired. Now I was a target for those behind me. Being passed in the late stages of a race can be demoralizing, but it’s also what makes racing exciting. I was still running where I could, but the terrain made it very hard to move quickly. Instead of letting it get to me, I used this moment to rally some energy and pick up my pace.

I saw hazy lights poking through the fog in the distance. When I arrived, a volunteer was there to separate the 100 milers from the 110k runners. This was the fork I’d heard about back at the previous aid station. Both races were on the home stretch, navigating the notorious twists and turns of a bike trail called “Comfortably Numb”, but Gary thought it would be nice to send the longer race on a detour around the most disorienting section as a “bonus”. Oh how grateful I was to be a 110km runner.

Home Stretch

I was alone again. The trail was hard to navigate in the dark, but I was starting to make out lights of the village in the distance. When I reached a clearing with a proper view, I couldn’t believe how far below the lights were from the ridge I was standing on. Add this to the list of sections I’d completely underestimated. It just kept dragging on and on.

I have no idea how much water I was drinking at this point, and I certainly wasn’t eating anything. I was running on pure will. I looked at my watch and it said 110km, 17 hours. I’d missed my sub-17 hour goal and there was still 3.5km to go. My stomach was still in pain, but no worse than before. My banged up knee was sufficiently numb.

After what felt like ages later, the trail finally reached a road. I looked at my watch again and it said 135.5km. This was supposed to be the end. Goddamnit, Gary! The road was paved and followed a fence. I could just barely make out the pink flags and I almost took a wrong turn down a road. This was not the time for mistakes.

I was getting closer and closer. I was so desperate to stop, to rest, to see Malcolm. I couldn’t yet see the finish line, but the thought “You did it” kept repeating in my mind. I still had to hammer out the last few hundred metres, but I basked in the satisfaction of a job well done and a smile crept across my face. Despite feeling terrible during this slow jaunt along the road, it occurred to me that my legs had never felt this strong before. They had done everything I’d asked of them. Despite some mistakes with my nutrition and hydration, all that training had really paid off.

Moments later, I saw bright lights and some orange cones leading down into the back of the Riverside Resort. I could hear a voice on a loudspeaker. Seconds away now! Someone cheered me on as I rounded the final corner. I could see the finish line. Finally, it was over!

“What are doing to us, Gary??” My official finishing time was 17 hours and 43 minutes, good enough for 9th place. I was two hours “behind schedule”, but given the bout of hives, lost water bottles, rookie nutrition mistakes and a collision with a large boulder, I considered it a great success. So much had gone wrong on the day, but I had to remind myself how much had gone right. That’s the beauty of this sport. No matter how much you train and how much you prepare, you never know how everything’s going to pan out.

Post Race

Malcolm was there at the finish line in great spirits. He turned on his camera for some candid post-finish footage while I tried to process the whole thing. I changed my clothes and I ordered a burger from the BBQ tent. I gave Malcolm a recap of the previous 6.5 hours. “That was the hardest race I’ve ever done,” I said emphatically. “Gary’s a sadist”.

It took me 45 minutes to finish eating my burger, but once I got it down, my stomach felt much better. I sat down with Malcolm next to a crew of runners and supporters, including the 100 mile race winner, who had finished 12 hours earlier in an incredible time of 24 and a half hours. Despite how exhausted I was, I was already considering the prospect of the longer race the following year.

Malcolm and I waited a little while longer to see Freddie finish, and then drove back to the WAC to crash. I woke up the next morning feeling achey, but relatively not bad. My left knee, however, forgotten the night before, was suddenly making itself known and was looking a little bruised and swollen. While Malcolm and I packed up, I received a text from Martin who had finished that morning. We picked him up from the finish line (where he was camped) and drove to a cafe in Creekside. Sitting waiting for a table was Dom, the runner from Whitehorse who had out kicked me in the last section. We chatted about the race and the challenges of the last couple sections.

A younger guy was sitting next to him who had also ran the 110km race. “Did you hike the trail?”, he asked. I didn’t really understand, but then I realized I was wearing my PCT hat. “Oh right! Yeah, I hiked in 2016”, I replied. His name was Josh and he had thru-hiked in 2017. Small world! Not that I was all that surprised to find another hiker at one of these events. We talked about the number of thru-hikers that get into ultras after the trail. It’s something about “condensed adventure”, we agreed.

So that’s it for 2019. My big “A” race is now over. There will always be regrets, things you wished had gone differently, but I’m grateful for how everything worked out. I also grateful for my excellent crew/crew chief, Malcolm, and to my parents for housing me, feeding me and putting up with me during my final weeks of training.

This year was a big transition for me. After a series of injuries through 2017 and 2018, I finally returned to health, took measures to stay healthy, and knocked out some of my biggest training blocks ever. I feel as fit as I’ve ever been. I might try and sneak in another shot at the Grand Canyon R2R2R later this year, but otherwise, I look forward to shifting my energies to other things in the coming months, like finishing the build out of my van. More on that soon…

Ross Noble is a software developer, ultrarunner, podcaster and former van-dweller with a passion for the outdoors. He writes about running, cinema and anything else that interest him.

Montreal, QC